RC4 Wireless provides wireless lighting and motion technology for theatre, film, and television. The company was founded by James David Smith — you can call him Jim — in 1991, after several years of providing custom wireless lighting systems for some of the largest theatrical productions in the world, including two productions of The Phantom of the Opera. Customers include Cirque Du Soleil, Disney, and Blue Man Group. RC4 systems are used at The Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, The Metropolitan Opera House, The American Airlines Center / Roundabout Theater, and Radio City Music Hall in New York City; The Sydney Opera House in Australia; the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, Canada; Disneyland in Anaheim, California; and many other performance facilities large and small.

Below, Jim reflects on the road that has led him to this place as leader in wireless lighting, motion, and effects for entertainment projects around the the world.

** ** **

I stumbled on an old audio cassette tape recently, a recording of one of my piano lessons when I was 10 years old. Originally there had been one 30-minute lesson on each side of this 60-minute tape, each side marked with my mother’s neat handwriting as “Jimmy Piano Lesson” with the date. But some time later, fascinated with recording and playing back all manner of other things, I recorded over one side with something far less interesting or meaningful.

Today, when I listen to the lesson recording that remains, two thoughts come to mind. First, I was playing rather well for a 10 year old. Second, as I worked through a Clementi sonatina, it was obvious that the teacher was the artist and I was simply there to operate the machine.

The very next year after that recording was made — at age 11 — I convinced my parents to loan me the money to purchase a Heathkit computer, promising to pay back every penny from paper-route earnings. After much negotiation of terms, they agreed. Off we went to the Heathkit store to get an entire AMC Gremlin-load of not-yet-assembled electronic equipment.

In it’s heyday, Heathkit was to electronics what Ikea is to furniture today. They made every attempt to get the kit builder through the process successfully. Instruction manuals divided the most complex tasks into bite-size little steps that even a child could manage. And there I was, proving this to be a fact.

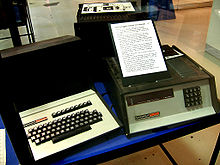

Heathkit H9 and H8

There are no records of how long it took me to assemble it all, but I can’t imagine it happening in less than several weeks, working whenever I wasn’t in school, or delivering papers, or practicing the piano. (A minimum of 30 minutes per day at the piano was required of me.)

Although this was the time of the Commodore PET and the Radio Shack TRS-80, the Heathkit machine was something entirely different. My system consisted of an H8 CPU, and a separate H9 terminal. Having spent what felt like the better part of my lifetime building the CPU, with the terminal not yet begun, I was eager for reward. What could I do with this thing? The basic H8 had nothing but a row of nine 7-segment numeric LEDs and a 4 x 4 numeric keypad on its front panel. Little could be done without the terminal, other than read and write octal values into memory locations.

(Octal is base-8, rather than our familiar base-10 counting, and uses only the digits 0-7. The appeal in early computing was that this conveniently aligns with the binary values expressed with 3 digital bits. Even my young mind questioned the advantage, however, given that memory values used a total of 8 bits. An 8-bit byte expressed in octal requires 3 digits: the top 2 bits (0-3), the middle 3 bits (0-7), and the bottom 3 digits (0-7). So… if you wanted the decimal value 255, you would enter 377. That’s the highest you can count with only 8 bits. Hexadecimal counting, using the digits 0-9 and letters A-F for a total of 16 characters, has usurped octal for good reason: one character represents 4 bits and 2 characters make an 8-bit byte. Decimal 255 is hexadecimal FF. As digital busses widen, simply add one character for each additional 4-bits. The highest integer value you can express in 32 bits is thus FFFFFFFF. That’s decimal 4294967295. )

My first computer program, written with absolutely no prior experience, was a digital clock with alarm. I figured out how to “poke” the memory locations that represented digits on the LED display, and — luckily — found that there was a digital bit for each of the seven segments. Thus, I could display the numbers 8 and 9, by writing a program for that purpose. (I used empty loops to waste time between each incremented second, resulting in a clock that was incapable of keeping accurate time. It would be years before I learned the proper way to create a steady timebase by using ‘interrupts’.)

This was machine-language programming, setting the stage for what I do today. Most firmware I write now is in the computer language C. Sometimes I use Basic. But I still occasionally write segments in assembly-language when I need the highest possible performance in the smallest possible code space.

By the time I started high school, in an effort to expand my musical horizons beyond Bach, Haydn, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky, and perhaps in hopes of winning the attention of a pretty girl, I taught myself to play guitar, bass, and drums. Working as a dishwasher at a banquet hall, I saved enough money to buy an electronic keyboard — a synthesizer. Music was my passion.

Based largely on an article in a hobby electronics magazine, I built a guitar effects pedal. Within days of showing off my odd contraption at school, which featured big round plywood wheels you could turn with your foot, another student — a complete stranger to me — offered $300 for it. I was shocked! It would take 63 hours of dishwashing to earn that amount of money, more than a month of part-time shifts. Sold! Besides, I thought to myself, I could build another one. There were things I would do differently next time.

My entrepreneurial spirit awoke.

I soon discovered there were quite a few things I could do for money, all of which paid considerably better and were much more satisfying than washing dishes. I learned to tune pianos and soon got on the list of tuners being called regularly by public and high schools in Toronto; and that was while I was still a high-school student in the same system! Then, at the age of 17, I joined a small improv comedy troupe as their “musical director”. They would make stuff up — some of which was actually funny — on stage while I followed along and did the same on the piano. FUN!

One of my favorite musical instrument stores, Long and McQuade, was expanding and hiring. Though I enjoyed being self-employed, I also yearned for more human interaction, and I had come to know and trust several of the people who already worked at this shop. I applied for an entry-level sales job and got it. Later I moved to the repair department. Moving my way up the ladder, I was eventually in charge of keyboard instrument repair. Still young, I was oblivious to how valuable my unusual combination of talents really was: I was equally comfortable tuning a grand piano or a Fender Rhodes electric piano; with finding a blown integrated-circuit in a Prophet-5 synthesizer or replacing a faulty disk drive in an Emulator sampler.

When a local theatrical producer built the Toronto production of Les Miserables, they came to L&M to lease and buy instruments and sound equipment. There was one item on their list that puzzled everyone; it could not be found in the catalog of any supplier. The New York Broadway show had annotated the scores for the keyboard instruments in the orchestra with references to an LED indicator displaying the settings of various electronic volume pedals. I offered to design and custom-build these devices, since they didn’t exist commercially. My manager suggested that I go ahead and make a deal directly with the client, which I happily did.

Thus, my first custom electronic device for theatre was in the biggest show of the day. Pure luck… plain and simple.

During this time, one of my closest friends, John Preketes, was off at university studying electrical engineering. As I learned the ins and outs of day-to-day business and customer service, and he studied the behavior of electrons while cramming for calculus exams, we planned to start an engineering company when he graduated.

And so we did. Prezmith Engineering produced a series of small accessory products for musicians. The Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) was newly introduced, and we jumped on the band wagon with through-boxes and data switchers. We developed a reputation for reliable custom engineering when required, and got the job to design — entirely from scratch — a complex programmable paging system for the renovated and refurbished Elgin-Wintergarden Theatre in downtown Toronto. (Our system is still in use today, more than 20 years later. The first service call came just last year — 2010 — where I found and replaced a small switching transistor that had failed.)

The Prezmith office was a unit in a warehouse building downtown, not far from an electronics supplier we used regularly. One mid-September afternoon in 1989, I rode my bicycle from our office to that supplier, and was roaming the aisles when our account manager approached me. “Jim — I’ve got a guy standing at the counter asking me all kinds of questions I can’t answer about transistors and remote control and smoke and something about The Phantom of the Opera. Maybe you could help him?”

I had only a murky idea of what The Phantom of the Opera was, despite it already being a blockbuster hit in London and New York.

Less than two hours later, John and I were standing on the stage of the Pantages Theatre, staring at a remote-controlled Phantom gondola. Someone had modified a hobby airplane controller with custom electronics to power the motors. Sometimes it worked well, they explained, but then, with a puff of smoke and an acrid smell, the whole piece would bolt at top speed, almost unstoppable. So far — luckily — the most damage it had done was a crash into the back wall, scraping some paint and bending the front of the gondola. But some day, they all feared, it would barrel towards the orchestra pit.

Opening night was less than 3 days away. The producers of Phantom knew nothing about the two twenty-somethings standing on their stage. But, at the end of their rope with almost all hope lost, with reassuring and confident words flowing off my tongue with aplomb, they gave us the job to make it right. We worked all day and all night, first figuring out what had been done, then determining why that didn’t always work, and finally coming up with an alternative. Our warehouse space was too small and cluttered to properly test this large set piece inside, so we drove it around in the hallway, telling other tenants our story as we drove back and forth over the extension cords powering our soldering irons. That Phantom boat worked perfectly for opening night, and continued to work for the run of the show.

The producer was Live Entertainment Corporation — (the now infamous) Livent.

Numerous other remote-controlled props and set pieces misbehaved in that show, and we got the job to rebuild them all over the course of several months: the music box monkey clapping its cymbals, the candle that throws a ball of fire, small lamps hidden in various places. We became the go-to people for remote control and battery-powered devices in any show Livent built. And they built many.

But, despite several prestigious projects in our portfolio, Prezmith Engineering was struggling financially. Major brands were now making MIDI devices in quantities and at prices we could not compete with. Our custom projects were consuming all our time, but not actually earning enough to pay all the bills. We had crates of products nobody would buy, and we were out of pocket for the costs of building them. Only two years after incorporating, my partner and I settled our debts and Prezmith Engineering closed.

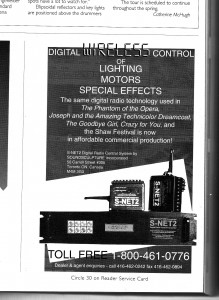

In 1991, determined to learn from my mistakes, I incorporated the company name I had first registered as a sole proprietorship in 1984 and Soundsculpture Incorporated was born. Free of the burdens that had crumbled Prezmith, I focused on remote control for theatre. The Soundsculpture S-NET2 — Soundsculpture Network Version 2 — was my first generic programmable wireless dimming system. I say “generic” because it was not designed for the needs of a specific show; it was designed to offer everything anyone had ever asked for, along with a few extras I anticipated would be asked for soon. A rack-mount transmitter wirelessly communicated with remote receiver-dimmers. DMX control was in its infancy and most shows did not yet use it. Instead, the S-NET2 had analog voltage (CV) inputs.

The news of my success with Livent made it’s way to New York City prop shops, leading to work on Broadway productions in the 1990s, including Neil Simon’s The Goodbye Girl (starring Bernadette Peters and Martin Short). Disney discovered S-NET2 and used it in two productions of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast. I began running US national magazine advertising for the first time. Business was good.

Then came RC3 — Soundsculpture Radio Control 3. Using a DMX to CV converter from Gray Interfaces (later to become Pathway), the RC3 was compatible with both analog and digital lighting control desks. But the real breakthrough with RC3 was the radio technology: this was the first time digital spread-spectrum radio was used for control of theatrical lighting.

By the time I launched the RC4 system — Radio Control 4 — I had not designed an audio or music device in a decade. Digital wireless lighting control was my business, and the name Soundsculpture Incorporated seemed altogether inappropriate. I learned about registered tradenames, which allow a business to operate under an alternate moniker without separate accounting records and tax filings. to this day, RC4 Wireless is a tradename of Soundsculpture Incorporated.

During this period in history, the Internet had appeared and, despite slow connections over telephone modems, was gaining traction. Shortly after I registered RC4 Wireless, I learned about web servers and HTML code, and created dev.rc4wireless.com. Today, almost all of my business is done right here, online.

As if all that weren’t enough, I went off on two tangents, exploring other kinds of business. From 1996 to 2000, I owned and operated a cassette and CD duplication company. Our customers were independent musicians, and I saw tremendous potential for the Internet to impact how musicians reach audiences. With the help of a software developer who doubled as our in-house audio mastering engineer, we built a website for musicians to post music on the web. We proposed giving away one or two songs, then charging $1 for the rest of the songs in an album. Use the Internet to earn a living with your music, we pitched hopefully. Despite being well-built and fully functional, the project was a complete failure. Neither musicians nor listeners were interested enough to reach critical mass. The limited few who could get music to play on their computers demanded that it all be free. We were accused of standing in the way of the socialization of music, of the return of music to its rightful owners. Funny how it doesn’t seem to have ended up that way. We had a great idea five years too early. I sold the duplication company, along with the website, and the buyer was, unfortunately, unable to keep it afloat for very long after.

My other side trip was considerably more successful. From 2000 – 2005 I was Chief Technology Officer for Revolution Display Systems. Along with Rikk Villa, we developed scrolling advertising signs that could be choreographed to create stunning large-format visual effects. Our efforts culminated in the design, manufacture, and installation of the world’s largest and most sophisticated scrolling sign installation in the world: the Toys R Us Building Board in Times Square, New York City. A huge matrix of one hundred and sixty-five signs, each 5 feet wide and 6 feet tall, spanned three faces of the Toys R Us store at the corner of Broadway and West 44th street. When the huge multi-face image scrolled from one advertiser image to the next, a spell-binding choreography would ensue that used time and speed of each individual sign to create a sweeping effect across the face of the entire building. I personally wrote every line of firmware that enabled effects to be created and displayed — it was years of work. Although the Toys R Us system is no longer being used, online videos can still be found on the Revolution website. To me, they still look breathtaking.

Today, back at the helm of RC4 Wireless, I couldn’t be happier. And I continue to break new ground, adding features and keeping my wireless systems at the forefront of innovation. RC4 offers the smallest dimmers; the safest motion control; the smoothest LED dimming; the widest range of useful parameters. This is my passion, and I stand behind my work. If wireless dimming and motion is what you need, rest assured there is nobody doing it better. Let me know how I can help.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. I look forward to doing business with you. Now, this being a gray Sunday afternoon, I’m off to practice that same Clementi sonatina that was the focus of a piano lesson 35 years ago. But today I am both the artist and the machine operator, developing my own interpretation of where the exposition ends and the development begins. And I do thoroughly enjoy it, even if I don’t always complete my requisite 30 minutes per day.

James David Smith

James David Smith

Toronto

6-Feb-2011

Revised and updated:

Raleigh, NC

14-Mar-2013